EoM Senior Interviewer Thomas Manning recently attended the Nashville Film Festival on behalf of Meet Me at the Movies. While there, he sat down with filmmaker David Fortune to discuss his feature film directorial debut, Color Book. This interview capped a busy day for Fortune in which he had already co-hosted a panel at the festival, screened his film with an audience, and engaged in conversation with dozens of viewers. Fortune talks to Manning about the casting process, representing the city of Atlanta on film, and the empathetic potential of cinema.

The official synopsis for Color Book is as follows: “Following his wife’s recent passing, single father Lucky (William Catlett) finds himself navigating the challenges of raising his son Mason (Jeremiah Alexander Daniels), who has Down syndrome. Seeking solace, Lucky and Mason embark on a journey across Metro Atlanta to attend their first baseball game together. Throughout their day-long trip, they encounter Murphy’s Law. From car breakdowns to missed trains, the duo faces a series of obstacles that test their relationship with each other. Despite the setbacks, they persevere, determined to reach the game. Color Book provides an intimate portrait of a father and son while exploring the experiences of raising a child with Down syndrome, highlighting the strength and resilience that emerge from their bond.”

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Thomas Manning: Like you talked about at the panel earlier, casting is [a big part] of the battle. And I really love who you brought together [in this cast] with William Catlett and Jeremiah Alexander Daniels. So I’ll just ask first off about finding them and realizing that they were exactly who you wanted to bring this to life. Can you talk about your first meetings with them and what clicked?

David Fortune: So, Will was someone from the early beginnings. He was in my lookbook. So I knew I was going for him. My lookbook a year in advance, Will was already in sight. And how we got a chance to reach out and contact Will is that, instead of going through his agents, we went through his people that he went to church with. So, Will was hearing about this movie while he was in church. His assistant would come up to him, “Hey, you heard about this film called Color Book?” His friend at church would be like, “Hey, have you heard about this film called Color Book?” He was getting hit with Color Book everywhere he went, and he was like, “What the hell is this film Color Book?” Finally, he was overseas doing a television series, but we ended up getting on a Zoom call. The first thing he really asked me was, “Whoever plays Mason, will they have Down syndrome?” And I was like, “Of course.” He was like, “Okay, step one complete.” Because that was important to him. He didn’t want to work with a child who was going to be pretending to have Down syndrome. He really wanted to engage with a child who had the disability. Because he just really wanted that experience to father them and to really engage with them and have that experience for himself. From that moment on, he was always locked in to do the movie. With Jeremiah Daniels, the process of casting him was a little bit more difficult, because we tried to put out a large casting call nationwide and we didn’t really get any responses. Because a lot of parents might not know or be aware of opportunities to put their children in acting, and also there’s that fear of how [their] child is going to be portrayed and protected on set. One of our producers was just reaching out to one of her friends who potentially had networks to financing. Her friend was like, “Oh, you’re doing a movie about a child who has Down syndrome? Have you guys cast the role yet?” [The producer] was like “No, we’re still looking.” Then [the friend] was like, “Well, I have a cousin who has Down syndrome and he has a personality. Can you audition him?” And [the producer] was like “Of course.” So he actually did a Zoom call. And in that Zoom call, he smiled, and as a result, everyone smiled. We all started cheesing and we couldn’t understand why. It was contagious.

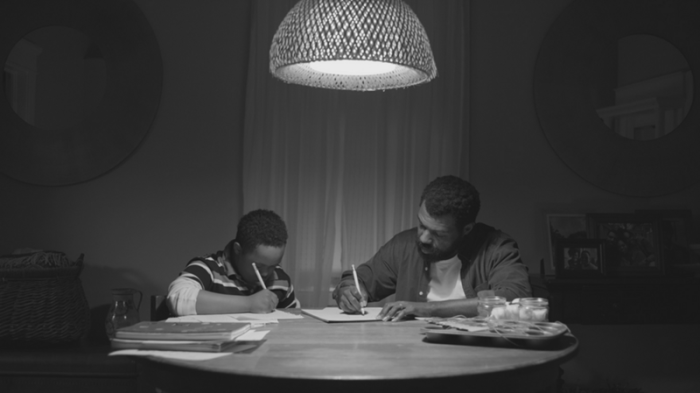

A scene from David Fortune’s COLOR BOOK. Photo courtesy of Autumn Bailey Entertainment/KiahCan Productions.

Thomas Manning: I felt that exact same way watching the movie. Whenever I saw him smile, I just couldn’t help myself.

David Fortune: To me, it’s infectious, but in a beautiful way. And from there on, we were like, let’s bring him in for a chemistry read with Will Catlett because he was still fresh, still new. And in that chemistry read, you could feel the instant bond between them. For me, it was just like… if that’s the experience we’re having in real life, that’s the experience I want to be showing on the film screen. It just felt so natural between them. That’s why I give all the credit to them.

Thomas Manning: Do you think we’re moving in the right direction with actors who are actually representing the Down syndrome community or people on the autism spectrum? There have been instances in the past few years, like Zach Gotsaggen in The Peanut Butter Falcon. Do you see that we’re moving where we need to be going?

David Fortune: I think we’re moving in the right direction. I just don’t think we’re moving fast enough. You have these films that come out every so often, but if this is a normal experience between many parents and their children, these should be normal cinematic experiences that we’re having on a weekly, monthly, and yearly basis. It shouldn’t be a surprise when a film like Color Book comes out. These should be normal occurrences. For me, that’s the main thing of getting Color Book out there – to encourage more people to tell their stories. Because these are normal situations that occur daily. If these are experiences we’re having daily, then these are things we should be seeing in cinema daily. I think that just happens with more films continuing to be pushed out and made. But that’s hard to do when you don’t have companies who are backing to support it. It starts from the larger problem of who is supporting our stories and getting them on board.

Thomas Manning: Something that I loved about the film from a sound perspective is that you just allowed us to sit in silence and embrace the silence. Was that something that was important to you from the very beginning, even in writing the script?

David Fortune: Oh yeah, for sure. For me, silence is important because it allows you to reflect. It gives you a moment to sit and understand what’s happening in this moment. Sometimes music could move the scene and push the scene in a direction, and we don’t get a chance to be present. I think having silence and having those quiet moments keeps us present in what’s happening and understanding the value that’s taking place at this present moment. That was kind of my goal with utilizing silence and music. Music involves you in the present emotion, but silence values the moment that’s happening – because we’re not moving on, we’re not pushing ahead. No, we’re pushing down, we’re locking down into this moment happening between father and son.

Thomas Manning: And in that same regard, you balance sounds of the natural world with sounds of the hustle and bustle of metro areas. I didn’t feel like it leaned too heavily in one direction or the other. Was that something you were conscious of?

David Fortune: Yeah. Something I discussed with my composer is that yes, we’re going to have musical score, but we wanted the natural sounds to be the score of this film as well. The crows crowin – we feel the tension of that scene. The train bustling – we feel what it’s like to be seated on that train and the emotions that come with it. Sometimes the natural sounds create score that still give you those emotions and those feels without the violins or cellos or horns or flutes. We’re allowed to just be present because we’re hearing the birds, the wind, the spinning fan, and it’s giving those emotions without a score.

Thomas Manning: The authenticity and emotionality just reached me on a very deep level. And I think a scene early on that really caught me was the funeral. The stories they’re sharing, the comments they’re making – were those written, or did you give the actors an idea of what’s going on and let them build from their own standpoint?

David Fortune: With that scene, nothing was written. Everything was being provided through a scenario of, “What is your relationship with Tammy?” How I approached it was: find the Tammy in your own life. Who’s Tammy to you in your own life? If Tammy is a 43-year-old woman and you are 47, Tammy could be your younger cousin. Tell the story of your younger cousin and just replace them with Tammy. Every story that you were hearing were true stories about people in their family. It was just replaced with Tammy. It made it feel more natural because now they’re telling the real story, they’re not having to make up and fabricate a moment – they’re telling something that really happened in their lives with another person or a cousin or a relative or significant other. It just kept that moment real and honest.

Thomas Manning: And is that something you’ve done on your previous projects, giving [the actors] something to pull from personally like that?

David Fortune: Of course. Because now they’re not thinking about it, they’re not performing – they’re existing, they’re living. It’s something truly resonant to their lives. That’s a technique I often employ, but I try to employ understanding that each situation is different, each movie is different. So you’ve got to cater towards the actual moment that’s taking place at that point in time.

Thomas Manning: Another scene that stood out to me: when they’re on the train and Meech [played by Njema Williams], the friend of [William Catlett’s character, Lucky] asks him generally how he’s doing. [Lucky] brushes it off, but then Meech looks him dead in the eyes and is like, “No, how are you doing, man?” Can you take me back to that moment? Do you recall anything specifically on set that day in what you saw that made that come together, and maybe why it reached me as it did?

David Fortune: You know, nothing special about that moment on set. We all knew the gravity of it from the screenplay. We always talked about, like, that was the main standout from the screenplay. So there was nothing about that day that was odd or new or interesting. What was honest was their connection in that scene – them both being two men that live life, that understand what it’s like to share emotion, but also understand what it’s like to hold back emotion. What I noticed was that we didn’t need many takes. It was already there naturally. I didn’t really direct it much. I just said, “Hey, go.” They got it and they took it and made it their own. I trusted each of their performances. I trusted each of them as actors. So there was no heavy direction. There was no, “Hey, you do this, you do that.” It was just more like, “Yo, let’s have this conversation.”

Thomas Manning: And it feels like that’s important to you to represent healthy masculinity in that way. Can you expand on that?

David Fortune: For me, it was two people seeing each other.

Thomas Manning: I think that’s what this film is. The entire film.

David Fortune: Two people seeing their wounds. So it’s not even about friendship, not about making a comment on masculinity – it was just as human beings, “I’m seeing someone hurt and I’m checking in.” It’s about another human being who is dealing with hurt but he’s not ready to reveal it. And the truth of that reality, and how it reflects all of our lives. Because as men, we always are guarded with our emotion. I wanted to paint a picture of what that truly looks like.

Thomas Manning: That’s special, man. And I love the repetition of the prayer as they’re sitting down to eat. We hear the same prayer every time. Was that something you grew up with, or where did you pull from for that?

David Fortune: My mom is a minister and my sister is a minister as well. We grew up in a home where spirituality was a priority. Honestly, the use of that scene really stemmed from – we’re walking into their home. We’re getting an understanding of what their customs and rituals are. They’re not performing that for us – they’re performing that for themselves. With this movie, we’re guests into their home, we’re guests into their world. That’s going to take place whether we’re watching the film or not. This is something that they do on a day-to-day basis.

Thomas Manning: Back at the screenwriting panel, you talked about having to cut a lot, you had to kill your darling a lot with this film. Was there anything specifically in that 20 pages that you cut out that you wish, if you’d had your way, you could’ve seen that come into fruition on the screen?

David Fortune: There was a scene where Mason has an accident on the train and Lucky has to rush him out and get him to the bathroom. We see Mason has struggled with wetting himself. And towards the end, the scene when we go back to the diner, Lucky asks Mason [if he needs] to use the restroom. Mason says yes, uses the restroom, and comes back out dry this time. We see Mason’s arc. And that’s kind of what I miss, is seeing Mason’s arc. [In the final cut], Mason’s arc is through the drawing, and that’s still apparent, but I do miss that arc of Mason going to the bathroom and trying to manage his accidents that he struggles with, and also going to later on in the story, him overcoming that. To me, I felt like that gave him his own little unique story. So I do reflect on that scene from time to time.

Thomas Manning: This is an Atlanta movie through and through. You were born and raised in Atlanta—

David Fortune: Well, I was born in Brooklyn, New York, but raised in Atlanta.

Thomas Manning: Raised in Atlanta. And you said you grew up in Decatur. Outside of what we see in this film, how has the city of Atlanta formed who you are creatively and continues to form your identity as a filmmaker – maybe in ways that wouldn’t be apparent on the surface level?

David Fortune: Atlanta created who I am. I grew up in Decatur, Georgia, which is about 15 minutes outside, depending on how fast you drive. That informed me, that raised me, that provided my perspective on empathy. That provided my perspective of how to show and depict and look at Black men. Showing that these individuals aren’t one thing – they’re many things, they’re complex. And that complexity reflects their humanity. And that humanity is what I aim to capture and reflect on screen. That all comes from my experience growing up in Decatur, Georgia, and the community members that I came in contact with throughout my journey in growing up as a young kid just trying to find his way in the city. So I owe everything to Decatur, Georgia and my ability to tell stories, because it derived from that space, from that community, and from those people who gave me the understanding of like, “Oh, yes, this person on the outside seems like an issue, but do you know the other side to them? [Because] I do.” So I say Atlanta has informed my empathy that I showcase characters with.

A scene from David Fortune’s COLOR BOOK. Photo courtesy of Autumn Bailey Entertainment/KiahCan Productions.

Thomas Manning: And as the great Roger Ebert said, movies are a machine that generates empathy. I think that’s fully on display in this film. Have you screened this film in Atlanta yet?

David Fortune: Yes, we screened at the Atlanta Film Festival. We’re going to be screening it next week at the Morehouse Human Rights Film Festival as well.

Thomas Manning: Do you think it hits even harder with the audiences there? Is there just something different in the air?

David Fortune: Yeah, because now they get a chance to see a reflection of themselves. They get to see themselves on screen. Their community, their friends. They get to see their neighborhoods. The places Lucky and Mason pass – they get to be excited to see that in film because normally they don’t. To me, it’s really special for the community to witness and watch.

Thomas Manning: Absolutely. Well, David, it’s been a pleasure. I’m glad we have filmmakers like you telling stories like this.

David Fortune: I appreciate it, and I’m glad we have journalists coming here to capture those stories. Thank you.

Official Synopsis:

Following his wife’s recent passing, single father Lucky finds himself navigating the challenges of raising his son Mason, who has Down syndrome. Seeking solace, Lucky and Mason embark on a journey across Metro Atlanta to attend their first baseball game together. Throughout their day-long trip, they encounter Murphy’s Law.

Screened during Nashville Film Festival 2025.

For more information, head to the official Nashville Film Festival Color Book webpage.

Thomas Manning is a member of the NCFCA, SEFCA, and CCA, and also the co-host of the television show and radio program Meet Me at the Movies. He has served as a production assistant and voting member on the Film Selection Committee for the Real to Reel Film Festival. Additionally, he manages his own film review and interview site, The Run-Down on Movies. Manning is a graduate of Gardner-Webb University with a double-major in Communications and English. His passion for cinema and storytelling is rivaled only by his love for the music of Taylor Swift.

Categories: Filmmaker Interviews

Leave a Reply